Employment, Poverty, and Race: Are they interconnected?

Before the mid-1960s, Canada’s immigration policies encouraged White Europeans to apply for immigration, and discouraged non-Whites from applying (Nakhaie, 2006). During the mid-1960s, European interest in immigrating to Canada dropped, causing a decline in Canada’s incoming immigrant population. Simultaneously, Canada was experiencing economic growth and needed technically and professionally skilled workers (Abu-Laban, 1998). After WWII, more humanitarian world views took hold in Canada, leading to the 1968 Immigration Act and 1978 Immigration Act which partially opened Canadian borders to non-White immigrants (Nakhaie, 2006).

The mid-1960s were a time of prosperity for immigrants. Employment terminations were rare, waiting periods were shorter for obtaining a first job, and full-time positions were common (Halli & Kazemipur, “Changing Color,” 2001). From the 1980s onward, poverty levels of immigrants have risen continuously. A study analyzing the 1996 census (see Table 1 below) found that the poorest subpopulations in Canada were all non-European, visible minorities – i.e. Non-Whites. The poorest are indigenous peoples (Nakhaie, 2006).

Table 1:

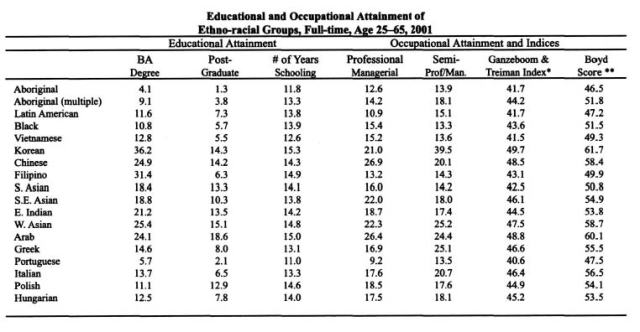

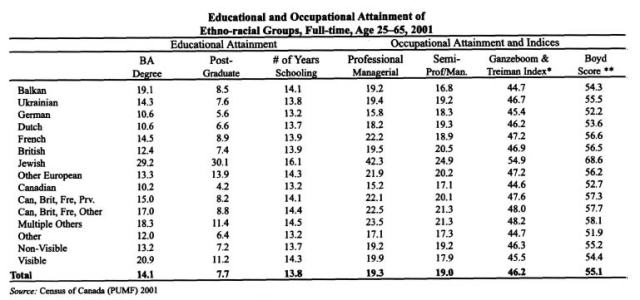

Why might this be the case? A popular explanation is that non-Whites have lower education levels, disqualifying them from better paying jobs. A study analyzing the 2001 census (see Tables 2 and 3 below) found that members of certain non-White immigrant communities – Korean, Chinese, East Indian, West Asian, South Asian, South-East Asian, and Arab – are more likely to hold post-graduate degrees than their White – English-Canadian, French-Canadian and most European – counterparts. However, these highly educated non-Whites held fewer professional/managerial jobs. This suggests that a lack of return on their education, rather than a lack of education, leads to poverty.

Table 2:

- Source: “A Comparison of the Earnings of the Canadian Native-Born and Immigrants, 2001,” p. 26

Another popular explanation for higher poverty among non-White immigrants is lack of familiarity with the social environment and lower official language fluency. According to this view, these immigrants’ children who grow up in Canada readily learn the language(s) and social norms. They assimilate more smoothly into Canadian society and experience greater job and financial success than their parents. The findings however, indicate that these children, who are better equipped culturally than their parents, are at higher risk for poverty, and fare worse than their parents (Halli & Kazemipur, “New Poverty,” 2001).

Table 3:

- Source: “A Comparison of the Earnings of the Canadian Native-Born and Immigrants, 2001,” p. 27

When educational requirements, language requirements, and cultural familiarity are not lacking, why are non-Whites consistently the poorest in Canada? One possible reason is a political and societal shift in attitudes towards non-Whites. During the 1980s and 1990s, the neo-liberal perspective was emerging. This perspective asserts individual responsibility for integration, cuts to government spending on social programs, and portrays marginalized groups – including immigrants and non-Whites – as social problems and enemies who steal education, jobs, and welfare of Canadians (Abu-Laban, 1998). This political discourse led to a tightening of immigration regulations. Simultaneously, studies from 1985 to 2000 suggest employers hired non-Whites less often, and when they did, the pay was lower (Nakhaie, 2006). Other research documents infer higher likelihood of employer refusals to recognize a non-White’s credentials, and higher likelihood of being screened out in the job application process because of language and racial characteristics (Li, 1998). If substantial research data strongly imply racial discrimination, and employers continue to treat qualified non-Whites as second-class citizens, how can Canada claim that it is not a racist society?

– Kajree Islam

Bibliography:

Abu-Laban, Yasmeen. “Welcome/STAY OUT: The contradiction of Canadian Integration and Immigration Policies at the Millenium(n1).” Canadian Ethnic Studies 30.3 (1998): 190-211.

This article discusses the changing political attitude – including neoliberalism – towards immigrants and non-whites in Canada, and how this influenced policy-making.

Halli, Shiva S. & Kazemipur Abdolmohammed. “Immigrants and ‘New Poverty’: The Case of Canada.” International Migration Review 35.4 (2001): 1129-1156.

This article mentions that poverty status was high for recent immigrants – higher for visible minorities – and that their children had higher poverty rates. This article also covers various factors – unrelated to ethnicity – that also contribute to poverty.

Halli, Shiva S. & Kazemipur, Abdolmohammad. “The Changing Colour of Poverty in Canada.” The Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology 38.2 (2001): 217-238.

This article describes how visible minorities experience less return from education and other forms of human capital, how/why they can end up living in poverty, and that they experience more discrimination than European immigrants.

Li, Peter S. “The Market Value and Social Value of Race.” Racism & Social Inequality in Canada. Ed. Vic Satzewich. Toronto: Thomson Educational Publishing, Inc., 1998. 115-130. Print.

The chapter (“Market Value”) in this textbook discusses the various employment barriers encountered more often by non-Whites. The author includes data on income disparities between non-Whites and Whites when equally qualified.

Nakhaie, M. Reza. “A Comparison of the Earnings of the Canadian Native-Born and Immigrants, 2001.” Canadian Ethnic Studies 38.2 (2006): 19-46.

This article discusses and describes pay inequities between visible minorities – Canadian-born and immigrants – and local Canadians of British origin, as well as lower education investment returns for visible minorities.

Canada is racist . period

Institutional Racism was a serious problem in the Library Science field when I tried to locate suitable employment after graduating from the UBC Library School back in 1988. Unable to find work here locally, I travelled to Toronto in search of employment. Although I did find work as a librarian back east, I did experience racism and racial attitudes from both my supervisors and even from some of my fellow co-workers. After struggling to make a go of this career for the next 4 years, I finally gave it up in 1992 and chose to go back to school to make a career change. Even Toronto’s reputation of being the “most multicultural” city in Canada in the late 1980s did not preclude the possibility of work place discrimination or employment discrimination for Canadians from a visible-minority background who were born in this country and who were also educated at Canadian post-secondary institutions. I can only imagine that systemic racism was a problem in many other institutions as well and not just the one I was most familiar with.

By “native born” Canadians you mean the WHITE ones who THINK they’re the “Natives.” Not us First Nations/Red Indians/Aboriginals.