It is not a secret that our culture and society look at certain situations and separate them on the basis of gender. One of the most prominent areas of society dominated by gender stereotypes and inequality is in the workforce. Gender-Based Occupational Segregation occurs when jobs are categorized as either inherently male or inherently female. Skilled trades have traditionally been defined as male occupations.

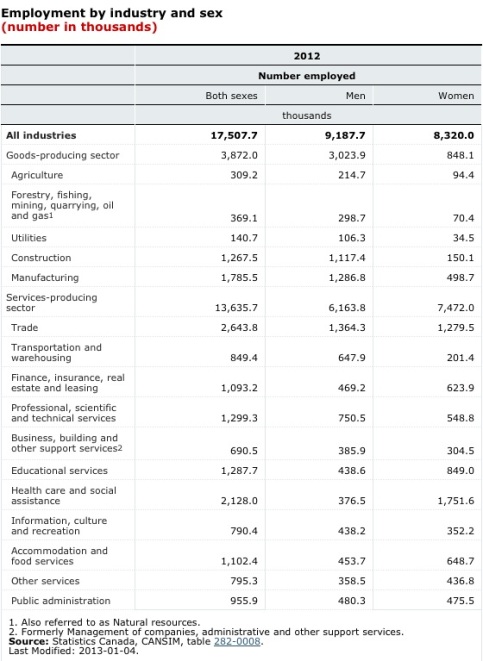

Skilled trades include jobs such as construction workers, electricians, welders and heavy equipment operators. Fewer than 3% of all apprentices in construction, automotive and industry trades are women (1). Statistics Canada also gives evidence from 2012 of a number of areas of gender inequality throughout the workforce, including skilled trades occupations (2).

One can argue that the government and workers unions have taken steps to close the gender gap in skilled trade occupations. For example, the Government of Canada implemented the Canada Labour Program which states:

Employment equity encourages the establishment of working conditions that are free of the barriers, corrects the conditions of disadvantage in employment and promotes the principle that employment equity requires special measures and the accommodation of differences for the four designated groups in Canada-Women, Aboriginal Peoples, persons with disabilities, and visible minorities (3)

This applies to both federal government bodies and to firms and institutions either financed or supervised by the Federal government. When it comes to skilled trades, employers must hire in accordance with the regional labour market levels of the four designated groups. So for example, if there are not many female construction workers, an employer is not required to hire many of them . The key barriers must be identified and solutions developed to increase the number of women who are interested in the training and employment opportunities associated with occupations in skilled trades.

The three main barriers women experience while trying to acquire training and employment in skilled trade occupations include: discrimination, lack of educational promotion, and inability of workplaces to implement effective strategies or change (4). Laws and policies (e.g. The Canada Labour Program) are only helpful if co mplied with by the employer, and they sometimes fail to ensure that women in this area of the workforce are not subject to discrimination. The lack of educational promotion concerns the trade schools and programs which tend to advertise and gravitate more towards recruiting men. While the inability of workplaces to implement strategies for change relates to the unchanging attitudes and stereotypes of employers and employees, who refuse to accept women in this area of the workforce. Or, employers who fail to take those actions, which will create an accepting environment. Organizations such as WiN Canada and Skills Compétences Canada have taken steps to address these issues and provide solutions to enforce change.

mplied with by the employer, and they sometimes fail to ensure that women in this area of the workforce are not subject to discrimination. The lack of educational promotion concerns the trade schools and programs which tend to advertise and gravitate more towards recruiting men. While the inability of workplaces to implement strategies for change relates to the unchanging attitudes and stereotypes of employers and employees, who refuse to accept women in this area of the workforce. Or, employers who fail to take those actions, which will create an accepting environment. Organizations such as WiN Canada and Skills Compétences Canada have taken steps to address these issues and provide solutions to enforce change.

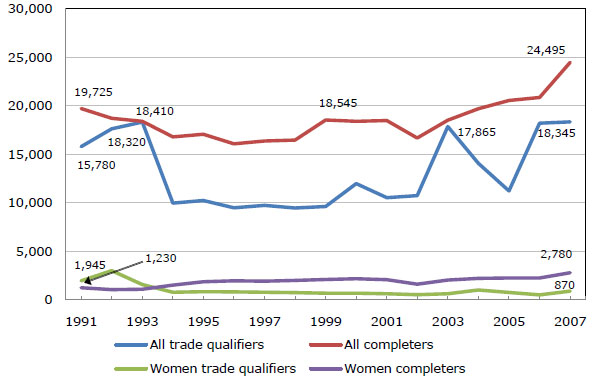

Trade Qualifications and Completions in Canada, 1991-2007.

Progress is still extremely slow and very little headway has been made since the early 90s. This can be seen in the sizable difference between all trade completion and women trade completion in registered apprenticeships between 1991 and 2007 (5).

Progress is still extremely slow and very little headway has been made since the early 90s. This can be seen in the sizable difference between all trade completion and women trade completion in registered apprenticeships between 1991 and 2007 (5).

It is estimated that over the next 5 to 10 years 40% of tradespeople currently in the workforce will need to be replaced due to retirement (1). Such a critical shortage in tradespeople will have a huge impact on Canada’s economy. Therefore, it is of utmost importance that the Canadian government, educational institutions, and employers work together to solve the problem of the shortages of women being employed in the skilled trade area of the workforce.

-Brittany Colbourne

Works Cited

(1) Smyth, Gail, and Cottrill, Cheryl. “Women Working in the Skilled Trades and Technologies” 2011. Web link.

(2) Statistics Canada, Employment by Industry and Sex, CANSIM, Table 282-0008.

(3) Government of Canada. Labour Program. Web link.

(4) Scullen, Jennifer, “Women in Male Dominated Trades: It’s Still a Man’s World,” Regina: Saskatchewan Apprenticeship and Trades Certification Commission, 2008.

(5) Statistics Canada, Registered Apprenticeship Information System, CANSIM, Table 477-0052.

Very important work. Thank you. I am an American older woman homeowner and have noticed the lack of women in repair services and also the preponderance of machines in so many areas of the trades which makes brute strength less important than it may have been at one time in the performance of this work. I also feel that male contractors and repairmen – and I have heard some of them say this themselves – discriminate against women clients by performing poor work, overcharging, and so forth. I believe more women in these trades would help raise the tone of work and improve the ethics and professionalism of these often well-paying jobs.